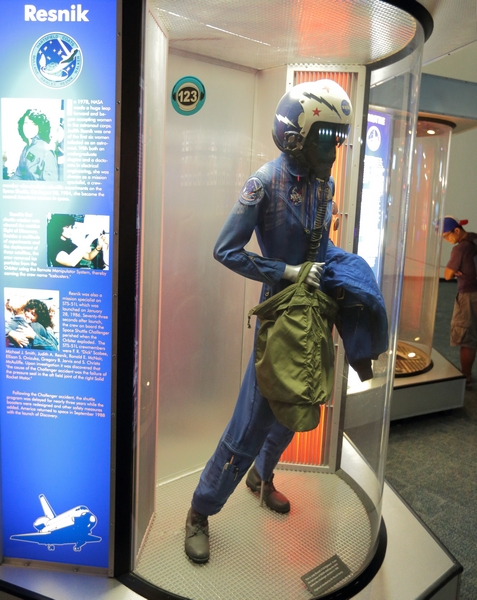

“Judy Resnik’s T-38 Flightsuit”

In 1984, Judith Resnik became the fourth woman and first Jewish American to travel into space. She perished when the Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff on January 28, 1986. It makes sense that a museum would want to display an artifact recalling Resnik’s life and I was not surprised when I happened across her T-38 Flightsuit at Space Center Houston on September 14, 2013 .

In 1984, Judith Resnik became the fourth woman and first Jewish American to travel into space. She perished when the Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff on January 28, 1986. It makes sense that a museum would want to display an artifact recalling Resnik’s life and I was not surprised when I happened across her T-38 Flightsuit at Space Center Houston on September 14, 2013 .

I have to admit that the Challenger disaster made a deep impression on me as a child. I still have a scrapbook of clippings from the period of the destruction and recovery of the orbiter. Yellowed with time, these clippings reflect both the posthumous crush that I had on Resnik (I wanted to be an astronaut) and the death of my mother only one month earlier from cancer. The day of the accident, I was not at school watching the launch with the rest of my 5th-8th grade class, but at home “sick.” The mission, you may recall, was a big deal because Christa McAuliffe was aboard as part of the Teacher in Space Program. Anyway, I’ve always questioned whether or not the footage I saw when I turned on the television that morning was live, or already playing in the endless loop that follows so many disasters.

All these memories flooded back as I gazed at the suit. But then I read the caption and puzzled over a short passage of the text: “Upon investigation it was discovered that ‘the cause of the Challenger accident was the failure of the pressure seal in the aft field joint of the right Solid Rocket Motor.’”

The o-ring failure in Challenger’s Solid Rocket Booster (SRBs) is well known, illustrated most dramatically by Physicist Richard Feynman, a member of the Rogers Commission that investigated the disaster, using ice water and two wood clamps in an open door committee hearing on February 11, 1986 (on YouTube, here). Yet to attribute the disaster to the failure of the o-ring alone misses much of what the Rogers Commission concluded about the accident.

My trip to Space Center Houston got me thinking about a book I read quite a few years back when I was working as a teaching assistant in an Aerospace Engineering class. That book was Apollo, Challenger, Columbia: The Decline of the Space Program (2005) by Phillip K. Tomkins. An expert in organizational communications, Tompkins had a long history working with NASA—in the Apollo years to understand what NASA was doing right and how the agency could be even better, and after Challenger, and then Columbia, to figure out what had gone wrong and how it could be fixed.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the most general sense the word “cause” refers to “that which produces an effect; that which gives rise to any action, phenomenon, or condition.” Perhaps the failure of an o-ring was the cause of the Challenger explosion itself, but there were a whole series of errors that led up to this final, ultimate failure. Drawing on the Rogers report, Tompkins identifies a series of communication failures that led to the o-ring failure, which caused the destruction of the orbiter. What it boils down to is that NASA management overruled Morton Thiokol engineers who questioned the safety of the SRB o-rings below 53 °F (it was 29 °F the morning of the launch). The space shuttle was cleared for launch in spite of the risk, and we know the results.

Tomkins says Feynman’s interview of three NASA engineers and their (uninvited) boss at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama during the course of the Rogers investigation was even more revealing than his ice water demonstration. When Feynman asked the four men to estimate the probability of failure for a space shuttle booster engine, two of the engineers estimated 1 in 200. The third engineer estimated 1 in 300, while their boss said 1 in 100,000.

Why, Feynman asked, did management so drastically underestimate the risk for failure? In Appendix F of the official Rogers Commission report, Feynman concluded, “One reason for this may be an attempt to assure the government of NASA perfection and success in order to ensure the supply of funds. The other may be that they sincerely believed it to be true, demonstrating an almost incredible lack of communication between themselves and their working engineers.”

The point—and the reason seven people died—is that NASA, once effective and successful, suffered when administrators began making the decisions, rather than engineers.